Families, colleagues in Louisiana, Georgia, and Virginia open up in wake of heart-wrenching losses. (Feature article – allow extra reading time.)

December 12, 2021 By Steven Kovac ~ The Epoch Times ~

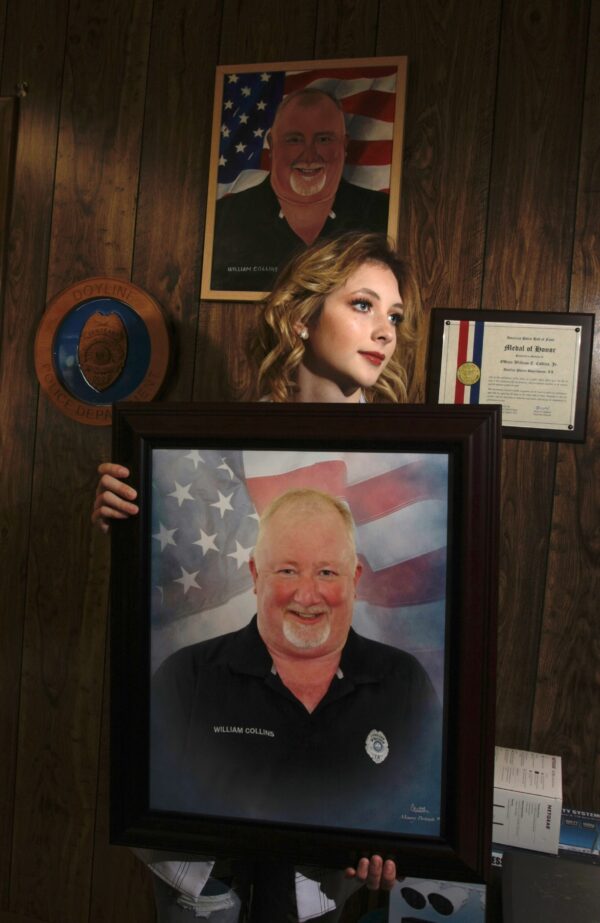

DOYLINE, La.—“Crinkle-cut fries are better than curly fries.”

And with that, Officer Billy Collins got the last word in on a long-running household controversy.

The joke was the last thing 17-year-old Danielle Collins heard from her father as she left the house to pick up the family’s dinner.

A far different domestic dispute was unfolding at a nearby residence at that very moment.

“At 5:45 p.m., we got the call that a suicidal guy with a gun was arguing with his wife and had fired a shot in the air,” Sgt. Coby Barton of the Webster Parish Sheriff’s Office said. “Billy got there three minutes before I did. The location was just 250 yards from his house.”

The scene was in the 400 block of Green Tree Road, in the little rural village of Doyline, Louisiana, a community of 800 residents policed by a two-person department.

That night, on July 9, 2021, Officer William “Billy” Earl Collins Jr. of the Doyline Police Department became one of the 28 cops killed by ambush in the United States in 2021, as of Nov. 30.

When Barton and Lt. Chuck Clark arrived on the scene, Collins was talking to a woman at the rear of his patrol car. Then shots rang out.

“It all happened in three or four seconds,” Barton said. “Billy was trying to protect the woman when a shot struck him in the right side of his head, and he went down. The second shot tore through my car. The third blast blew out the front passenger window of Chuck’s patrol car.”

The rounds came from a 12-gauge shotgun fired by the husband of the woman.

“He fired only three shots from just inside the front door of the trailer house. They were 3 1/2-inch magnum shells loaded with double-aught buck,” Barton said.

One large caliber pellet missed Barton’s head by an inch. Another went by six inches from his upper arm and shoulder. The holes remain in the interior of his car.

To Barton, those three or four seconds transpired in slow motion. He grabbed his rifle and a trauma kit and radioed, “Officer down!”

Barton took cover behind his patrol car as the woman screamed to him to come over to help Collins. Clark positioned his car near Barton’s to form a better shield for Collins and the woman. He then grabbed his rifle and got down on the ground. The only thing going through his mind was making sure everybody was safe.

After that, Barton said, things went eerily quiet. The shooting stopped. The hysterical woman “went catatonic.”

Only four shots had been fired, all by the deranged husband.

When asked why he and Clark hadn’t returned fire, Barton cited concern for the safety of those in the area.

“Once you send a round, you can’t take it back,” he said. “We couldn’t safely shoot back without the risk of hurting someone else. There are houses behind the trailer house. People were coming out of the woods back there to see what was going on.”

‘Our Covering Angels’

Clark, a big, rawboned, athletic-looking man, tried in vain to get Collins into Barton’s patrol car. For him and Barton, help couldn’t arrive fast enough.

Deputy Tommy Maddox was the first to arrive on the scene once the shooting stopped.

“Tommy’s got a fake leg, yet he ran up the 60-yard driveway into who knows what like Carl Lewis. He peeled off his vest and shirt and pressed them against Billy’s head as a bandage,” Barton said.

Soon other support officers appeared on the scene.

“I call them our covering angels. They positioned themselves to provide cover for us if needed,” Barton said.

Minutes later, Webster Parish’s Sheriff Jason Parker arrived and took command. He directed an arriving ambulance to the driveway where Collins was located. The downed officer was placed on a backboard and loaded in.

By this time, around 6 p.m., Danielle Collins had returned from the restaurant.

“I asked my Mom, ‘Where’s Dad?’ She answered, ‘He was dispatched on a call. Just a domestic dispute,’” Danielle said. “Right about then, one of my friends from school texted me the short message, ‘Officer Down.’

“Mom talked to a friend of hers on the phone, who has a police radio, and asked her, ‘What’s going on?’ ‘I don’t know. Just get to the baseball field!’

“The baseball field seemed to us the place where the Life-Flight helicopter could land. Though not confirmed, Mom and I now suspected it was my Dad.

“EMS was already there. We were met by the mayor [Stephen Bridwell] who said to us, ‘It’s him. Get to the hospital’ [Ochsner-LSU Hospital in Shreveport]. People offered to drive us, but Mom said she wanted to drive. She turned a 40-minute trip into 25.”

‘My Dad Was Shot in the Head’

On the way to the hospital, Danielle Collins reached out to family and friends to let them know what was happening.

“At the hospital, people were gathering in the Family Room,” she said. “Grandma [Billy’s mother] drove herself from Minden. My step-sister was on her way from Oklahoma. Because of COVID, they wouldn’t let everybody in. My best friend, my great aunt, and great uncle and the youth leader from my church weren’t allowed in, so I went outside to be with them.

“It was a waiting game. Someone was watching live footage of the standoff on Facebook. Someone else was live streaming updates. That’s how I found out my Dad was shot in the head. Then a nurse came out looking for me, saying my Mom wanted to see me.”

The National Fraternal Order of Police (NFOP) defines an ambush as an attack in which an officer is shot without any warning or opportunity to defend himself. A total of 119 law enforcement officers have been shot in 95 ambush-style attacks as of Nov. 30. The number of ambushes is up by 126 percent over the same period in 2020.

While the family was at the hospital, the standoff at the trailer home continued.

A total of 200 officers surrounded the home. Despite all that firepower, the first and only shot fired by law enforcement during the five-hour standoff was taken by Clark, when a police spotter pointed out what was thought to be the red dot of a laser coming through one of the trailer home’s windows. It wasn’t.

According to long-time Doyline Police Chief Robert Hayden, there was no response from the barricaded gunman. No reply to the officers’ repeated verbal appeals to surrender. Just silence.

Hayden said the Louisiana State Police SWAT team used flash-bang grenades to create a diversion in order to slip a small drone into the house.

“We tried to talk to him through the drone,” he said. “The main goal was to see to it that nobody else got hurt, even the suspect. I’ve known the man for 30 years. I knew him to possess an array of weapons.”

Through the drone’s camera, the subject was seen lying unresponsive on a bed. The decision was then made to go into the house. He was still alive. First responders attempted to save him.

“He’d shot himself in the chest with a 22-caliber pistol after taking two or three bottles of blood pressure medication,” Hayden said. “The only harm done to him was what he had done to himself. Every effort was made to do him no harm.

“He was airlifted to LSU Hospital, where he expired a week later.”

Devastating for the Community

About 2 1/2 hours after her father was shot, Danielle Collins learned from her mother that he had died. A few days later, Danielle would deliver a eulogy before more than 3,000 attendees at her father’s funeral service.

Chief Hayden said: “It was a sad time. It broke my heart. It’s still broke.

“I think of Billy every day. I knew him for 11 years. He worked for me for four. He was somebody I depended on. He was always there when I needed him.”

Collins’s death led the police chief to consider quitting law enforcement.

“The day he died, I went home and took off the uniform and threw it across the room. I said, ‘I’m done,’” Hayden said.

“I was done, until my wife said to me, ‘Would Billy have quit if you had died?’”

He wanted people to know that police officers are “human, too.”

“This has been very devastating to this God-loving community,” Hayden said. “This village is so quiet, especially in the evening.

“The typical incident we have to deal with around here is a complaint that somebody’s dog keeps pooping in the neighbor’s yard.”

Those living in the community were shocked by the killing.

“Stuff like this doesn’t happen around here,” said Eddie Hozam, the owner of a combination gas station and convenience store in Doyline.

“Billy was a regular customer. He was a cheerful man. Everybody loved him. And the fellow who shot him was also one of my customers. He was always nice to deal with.”

Lifelong resident Jody Carter said Collins was a positive influence in Doyline.

“He was always so calm and collected,” Carter said. “He would much rather help someone than get them in trouble.”

Speaking for the Collins family, Danielle thanked her father’s fellow officers for the support they provided the family after his death.

“We would not have made it through this without the love and support of Chief Hayden, Sheriff Parker, Lieutenant Clark, and Sergeant Barton,” she said. “I know if I ever need anything, I can call on those four men. They are more than friends. They are family.”

She also had a message for the sons and daughters of police officers across America.

“I want them to realize that you have to share your Dad, or Mom, with the community,” she said. “The sacrifice of serving in law enforcement is not just paid by the officer, but by his, or her, loved ones as well.

“Not knowing if a Dad, or Mom, will come home again is as big a sacrifice as that made by the one who goes off to duty every day.

“And to the children of officers who made the ultimate sacrifice, I say, keep your head held high. Make them proud. Show them by your life that their sacrifice was worth it.”

According to the NFOP, of the 314 officers shot in the line of duty in the first 11 months of 2021, 58 died.

Responding to domestic disputes, making traffic stops, and navigating vehicle chases are some of the most dangerous duties law enforcement officers face. The number of shootings—and the death toll—rises every week.

Car Chase

In Georgia, flashing blue lights were all it took to make Capt. Justin Bedwell’s patrol car a gunman’s target.

The deadly scenario began when two brothers from Tallahassee, Florida, both in their early 40s, stole their mother’s pickup truck and went to Georgia.

Their first encounter with the police started when a Seminole County law enforcement officer attempted to pull the pickup over. When the vehicle didn’t stop, a chase ensued, and the brothers opened fire at the pursuing patrol car.

Decatur County Sheriff Wiley Griffin described what happened next.

“Attempting to evade arrest, the brothers tore through residential yards and business parking lots, firing more shots as they fled,” Griffin said.

The hail of bullets disabled the pursuing police car, and the pickup sped away. By this time, patrol cars from nearby departments had joined the chase.

“Despite continued gunfire, pursuing units stayed in pursuit, but had to drop back to maintain a safe distance,” he said. “This caused them, at times, to lose visual contact with the pickup.

“Out there in the country, the nights are very dark. There are a lot of woods, and the houses are few and far between.”

When the brothers came to a T-junction in the road, they turned right and on to Brinson Colquitt Road, near the small city of Bainbridge, in Decatur County.

“By this time … Bedwell, of our department, was on his way to aid in the chase,” Griffin said.

The brothers had decided to get off the road and hole up at the first house they came to—the brick, ranch-style home of Jesse and Melissa Whitley.

“It was a completely random choice. It could have been your house, or my house,” Griffin said, adding, “Those boys picked the wrong house. The security camera gave the Whitleys warning. Then it caught the whole thing on video. Great evidence!

“Their door was solid and had a deadbolt lock. And Jesse was not just a gun owner—he was the type of guy to shoot back.”

Bullets Flying Through the House

The Whitleys were watching television over coffee in their den when Melissa glanced at the monitor of their security camera system. A white pickup truck had pulled up to the house.

“I told Jesse, ‘There’s a man walking around the backside of the house with a gun in his hand!’”

“Next thing you know, somebody is yelling, ‘Open the door! Let us in!’ And then, gunshots,” Jesse Whitley said. “I said to myself, ‘This ain’t happening!’ I was stunned.”

Melissa grabbed their little dog, and Jesse grabbed the two of them and put them in another room, where he thought they’d be safe.

“Bullets are flying through our house, through the drywall and ripping up the furniture. I hollered, ‘Get out of here!’” Jesse said.

“’We’re friendly! Open the door!’ That’s what they said. Weird.”

The brothers then ran around to the front porch.

“They were trying to shoot a circle around the deadbolt on our front door. It didn’t work. My Daddy made that door of solid wood,” Jesse said.

“The only loaded gun I could get to that wasn’t locked away was my 9-millimeter pistol.

“I grabbed it and shot two or three times through the door, through the wall beside the door, and through the window next to the door.

“I believe my last shot hit and disabled their shotgun. It didn’t fire again. We found out later it was put out of commission by a 9-millimeter round.

“Right about then, the one with the rifle opened up on a police car as it was driving by the house.”

A shot from that volley of bullets took Capt. Bedwell’s life.

“It was from the Whitleys’ yard that the fatal shot was fired,” Griffin said. “A bullet pierced the driver’s side door, striking Justin in the side of the chest, mortally wounding him.

“Our bulletproof vests go on like two halves of a clamshell. The front and back come together at the sides, leaving a narrow gap in the armor. The round came through the gap. What are the odds?”

A Real Professional

Communication problems also played a role in the incident, according to the sheriff.

“Bedwell drove past the Whitley property unaware of the latest status of the chase and unaware of the shootout at the house until he was fired upon. The closest unit did not know Bedwell got shot. This cost precious minutes,” Griffin said.

The first to get to Bedwell was Chief Deputy Wendell Cofer of the Decatur County Sheriff’s Office, a 38-year law enforcement veteran.

It took 13 minutes for Cofer to reach the scene. He was at a restaurant in Bainbridge having dinner with friends when news of the shooting reached him. He and a state trooper friend sped to the scene in Cofer’s personal car.

“Though mortally wounded, Justin pulled his patrol car out of the line of fire and radioed to us his exact location. He was a real professional,” Cofer said.

According to Griffin, after firing a volley of shots at Bedwell’s patrol car, the brothers jumped back into the truck and took off into a wooded field behind the Whitley home.

“The land was being cleared of trees,” he said. “I’m surprised the truck got as far as it did. They hit a stump that tore a wheel off it, so they split up and took off on foot.”

With officers from surrounding departments arriving on the scene, a perimeter was established, and tracking dogs and a helicopter equipped with infra-red technology were used to pursue the brothers.

Around midnight, the infra-red sensors on the chopper pinpointed one of the brothers hiding facedown in the field, less than 50 feet from the police line.

“Had he been armed, he could have shot an officer in the picket line and stolen his car,” Griffin said. “Fortunately, he didn’t have his gun. The weapon was found a short distance away in the field by a tracking dog.

“His brother was caught in some nearby woods the next day.”

Both shooters have been charged with felony murder and a dozen lesser charges.

They are being held without bail in two separate jails outside of Decatur County while they await trial at the county courthouse in Bainbridge in February 2022.

Bedwell’s wife, Katherine Bedwell, and 10-year-old step-daughter, Maddie Lue, were at home at the time of the shooting.

Maddie Lue was already asleep when a family friend, a former sheriff’s deputy, came to their door. The friend informed Katherine that her husband had been shot and that he was being airlifted to a hospital in Tallahassee.

Now widowed for eight months, a somber Katherine, dressed in black, shared the awful story.

“It helps me to talk about it,” she said. “I remember my first thought was, ‘This is not real.’ Then shock set in.

“Within minutes, people started showing up at the house. Our neighbor agreed to sit with our daughter. Friends helped me pack a bag for the hospital. A friend drove me there.

“When we finally arrived, Justin was already in surgery. Soon, word came that he survived the procedure. I stayed with him for 24 hours—until they told me I had to go home.”

Hours later, when Katherine returned to the hospital, she was denied access to the Intensive Care Unit.

“I learned Justin had coded [gone into cardiopulmonary arrest],” she said. “It was like a movie. They wanted me to go into a room and talk to doctors. I couldn’t bring myself to go in there. I didn’t want to hear it. I didn’t want it to be true.”

He had died just minutes before Katherine pulled up to the hospital.

Important to Get Counseling

Katherine Bedwell said she broke the news to Maddie Lue.

“Justin and Maddie Lue were inseparable. ‘Best buddies’ is what they called themselves. You would never know she was not his own daughter,” she said.

“This is the kind of man Justin was. Out of respect for Maddie Lue’s father, Justin and Maddie Lue created what they called ‘Best Buddy Day,’ something the two of them could celebrate in place of Father’s Day.

“I want to honor my husband’s name, not only as a law enforcement officer, but also as a husband, as a son, as a best buddy. He was a huge example of a hero. Justin was a phenomenal human being.”

She said, “I’m trying to put on a brave face. I fight the tears. But every day I’m living a nightmare. Some days are easier. Some days are terrible.”

She believes that when death comes to a household, any family members shouldn’t hesitate to seek mental health counseling. “It’s important. It can help,” she said.

“Grief is different for everyone. Own your grief. Try not to compare your grief with the grief of others.”

Katherine has lived in Bainbridge for nine years. For the past five years, she has taught at a public elementary school in the community.

“Through our jobs, we got to know a lot of people. Justin interacted with so many young people through many community activities, especially football,” she said. “So many of the students whose lives he touched have reached out to me. Even people he arrested years ago have reached out to me in sympathy. That says a lot about the kind of man he was.”

Katherine spoke fondly of the spontaneous demonstration of love and support she and Maddie Lue received when her husband’s body was brought back to his hometown from Tallahassee Memorial Hospital.

Bainbridge native Brice Flowers was working on a garbage truck that day. “They say the procession was seven miles long,” he said.

Katherine recalled: “As we entered Decatur County, thousands came out to line the streets as the procession went by. It was a satisfaction to see how this community thought so highly of my husband.

“So many people turned out, not only to comfort me and Maddie Lue, but, I believe, to comfort each other.

“This kind of tragedy is not supposed to happen here.”

Griffin said Bedwell’s funeral service had to be conducted at the high school football field because so many people wanted to attend.

Lt. John Presilla, Bedwell’s coworker, said: “Justin always urged us to be well-prepared. Ready for anything.

“Well, the most prepared guy among us got shot in a terrible way. It was a great loss. Justin was such a nice guy. Everybody loved him.

“I want to tell my brothers and sisters in law enforcement across America, love every day that you have, because you never know when it may be your last.”

Reducing the Toll

More and better training, both in-service at the department level and at police academies, is regarded as one of the keys to reducing the number of officers shot and killed in the line of duty.

“To prepare young people for the increasingly hazardous environment new recruits will be working in, we are setting robust standards and demanding academic rigor,” said Joe Kempa, section manager for career development at the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards.

The agency sets uniform academic standards for police training academies across the state.

“We analyze the frequency and criticality of a task, emphasizing the right way to handle firearms and how to properly use radio communication. Situational awareness is stressed, like parking the car, walking up to a home, and choosing the best location for a traffic stop,” Kempa said.

“We are teaching improved tactics—like the effective use of cover and concealment, even down to such things as how to operate safely in low-light situations. For example, we teach how to use your flashlight without making yourself a perfect silhouette.”

Kempa said that recruitment is down, but he believes this is more due to the economy than anything else.

Joe Ferrandino, director of the Criminal Justice Department at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, said enrollment in the criminal justice program is down, but he said the increased violence against police officers is not the sole cause of the decline.

As of Nov. 30, Texas led the nation with 42 police officers shot in the line of duty, followed by Illinois with 25 and California with 21. Michigan had four.

In the southeastern United States, 17 were shot in Florida, 17 in Georgia, 15 in Alabama, and 12 in North Carolina. These four states accounted for nearly one-fifth of the national total.

Missing Death by Inches

Mountain man Dwight Foster was driving his truck up the lane from his firewood pile when he saw the police cars lined up in front of his house in Stanley, Virginia.

“I looked to my left and saw a young fella with a rifle standing there in the barnyard just feet from me. I figured it was him they were lookin’ for. I rolled down the window and said, ‘Boy, what are you doing with that gun?’

“‘Shoot me,’ he says. I told him, ‘God loves you. Put that gun down.’”

Meanwhile, Chief Deputy Pete Monteleone of the Page County Sheriff’s Office advanced on foot from the road, moving slowly along the wall of a building, as other officers were closing in from all directions. He yelled at Foster, “Get out of there! Get out of there!”

Foster persisted, “Boy, no matter what you’ve done, God will forgive you. Let’s talk.”

“He didn’t get mad,” Foster recalled. “He never pointed his gun at me. He was polite. He said, ‘I’d rather be dead than go to prison.’

“I told him, ‘Going to prison, and then going to Heaven, is a whole lot better than dying here and going to Hell. Now put down your gun and let’s talk, or else you’ll have to get off my property.’”

When he got no further response, Foster eased his pickup down the little slope toward the back of the house where he was met by his frantic son, who handed him a gun.

The 29-year-old gunman, ignoring police commands to drop his weapon, walked about 30 feet and allegedly began to raise his Smith and Wesson M&P-15 rifle to a shooting position.

The one-hour manhunt ended the way it began, with gunfire and death.

“One of our deputies took him out,” Monteleone said tersely.

The whole thing started with a traffic stop on the quiet residential streets of a subdivision in Stanley, a little town at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Shenandoah Valley.

Officer Dominic “Nick” Winum of the Stanley Police Department spotted a 2002 Honda Civic that matched the description of a car driven by a man brandishing a gun and behaving erratically.

“Nick got two letters of the license plate number out on the radio. His body cam, especially the audio, told the story. He didn’t have a chance,” said Stanley’s Police Chief Ryan Dean.

According to Dean, the body-cam footage showed the driver jumping out of the car and opening fire. “He didn’t even take time to put it in park.”

More than 20 rounds tore through Winum’s vehicle. He was hit multiple times and died at the scene.

The shooter’s car rolled down Judy Lane and came to rest in a roadside bush. A handgun was later found in the vehicle.

The first officer on the scene was only a few hundred yards away when he heard the call.

“He got there while gun smoke still hung in the air. He took fire to his vehicle. Two or three rounds lodged in the front passenger-side headrest. He missed death by inches,” Dean said.

The shooter took off on foot, darting between homes and through yards, heading for the woods out back.

Monteleone said the subdivision’s residents became the eyes and ears of the police, peering out from behind draped windows and calling in reports.

Urged to Surrender

In danger of becoming targets themselves, officers pulled Winum’s body from his bullet-ridden car and laid him on the ground in the yard of a nearby house.

By now, 30 officers were on the scene. A perimeter was established around the neighborhood. The Stanley Fire Department helped block the roads.

“A gunman on the loose in a densely populated neighborhood is a real threat to the citizens. And this guy already demonstrated he was willing to kill,” Monteleone said.

“At a time like that, it’s a struggle to keep your composure. We encouraged one another. We followed our training. We got separation, regrouped, and re-engaged.”

Monteleone had a plan to apprehend Winum’s killer.

“Six or seven of us got together and decided to press after him hard. To keep him moving. To drive him like a deer into one of our lines. We knew he had a scope on his rifle. We did not want him to catch his breath and be able to hunker down and start taking good shots at us or others,” he said.

“I felt naked walking through those yards and fields. A round could go through the ratty old bullet-proof vests we had on like a hot knife through butter. We didn’t have the kind with the insertable armor plates in the front. We’ve got them now, after the fact.”

As the gauntlet tightened, pursuing police caught an occasional glimpse of the gunman and repeatedly urged him to surrender.

Dean said: “Our first response was around 3 p.m. The shooter was down a little after 4 p.m.”

He still gets emotional when he speaks of Winum’s slaying.

“Understand, including me, we are a five-member department in a little town of 1,900 that doesn’t even have a stoplight. Not only do we work together, we see each other outside of work four or five times a week.

“We’ve seen nothing like this in my 27 years. It was overwhelming. The first 10 or 12 days after Nick’s death were a blur.

“Until recently, about the worst thing we dealt with was fist-fighting with some drunken 40-year-old adolescent who decided to tear up a bar on Friday night.

“I’d break up the fight, subdue him, and arrest him. And later, he would come by the office to apologize. That’s the way it was. Not anymore.

“In the past, people used to run from us. Now, they run at us.”

How does the veteran chief account for the changing environment?

Shaking his head, Dean answered, “I don’t know.”

Stanley’s mayor, Michael Knight, dropped by the tiny police station and said of Winum: “Nick loved working with people in the community. He was a real person. I was devastated.”

Then Knight shared the news that two officers were shot in Rex, Georgia, the previous night. One of them died the next day.

“Stanley is a small town,” Knight said. “I know the shooter’s family. It’s a single-parent home. As a child, he was in trouble for stuff like throwing rocks at cars.

“The boy needed help. He needed mental health assistance. Though drugs may have played a part, this shooting was more mental health- than drug-related.”

Sheriff Chadwick Cubbage of Page County, population 24,000, believes the impact of the loss of a police officer is disproportionate in small communities and small departments where people are so well-known to one another.

“You don’t have to be a big department to be an elite and very professional department,” Cubbage said. “Nick Winum was a true professional. It was a real tragedy.”

Dean said that Winum had been with the Stanley PD since 2016.

“In all that time, I never heard a single complaint about him. He was a nice guy,” he said.

“On his lunch hour, he’d make it a point to eat with people and talk with them and pray with them. He was truly a difference-maker.”

Knight remembered the crowds that lined the streets of neighboring communities as they brought Winum’s body back to Stanley from the coroner’s office.

“Nick’s funeral service was so big it had to be held at the school football field. He was then driven to his home state of New York,” Dean said.

“At the New York state line, our procession was greeted by a motorcycle escort. First responder vehicles were on every overpass. The procession grew and grew as we neared his final resting place.”

As the news of the tragedy spread, Stanley residents and people from all over Page County began sending flowers and letters. They brought pictures, plaques, and food to the police station.

“Folks who I know can’t pay their water bill, and even people who Nick arrested in the past, donated money to help with funeral expenses,” said Dean.

Concerned About Others

Stanley PD’s school resource officer, Brian Puffinburger, said: “We are heartbroken. We never thought this kind of thing could happen in this community. Since Nick’s passing, when we go to work, we are being extra careful.”

Puffinburger talked of the extraordinary grace of Winum’s widow, Kara, who “saw to it that the church sent food to the shooter’s family.”

Stanley Police Captain Aaron Cubbage spoke of the close “brother-sister” relationship between Kara and the guys at the department, and of the selfless character of the Winums, who he described as the “all-American family—the kind of people that do good and don’t want anybody to know about it.”

The Winums have four grown children, two daughters and one son in the Marine Corps and one son serving in the Air Force.

The duty of breaking the news of Nick’s death to Kara fell to Chief Dean.

“When I told her, her first concern was about others,” he said.

Sitting in the conference room of the school where she teaches, Kara reflected on that awful day, now nine months ago.

“My focus was on our loss, not on how it happened. Anger never entered into it,” Kara said,

“Stanley, Page County, the state of Virginia, and America, lost a fine police officer. But I lost my husband. We were married for 27 years.”

Kara said that serving in law enforcement didn’t define Nick.

“If you were to ask him to describe himself, he would have said, ‘Number one, I’m a Christian, a husband, a father, a son, a brother, and a friend.’

“Nick had a strong sense of the line between right and wrong. He loved interacting with people. As a local law enforcement officer, he felt he would have more opportunity to have meaningful, more personal, interactions with people. That’s why he left the State Police.”

Referring to the shooter’s mother, Kara said: “There’s a woman across town with a very different grief. She must cope with the loss of her son without all the love and support of the community. My heart and prayers go out to her.”